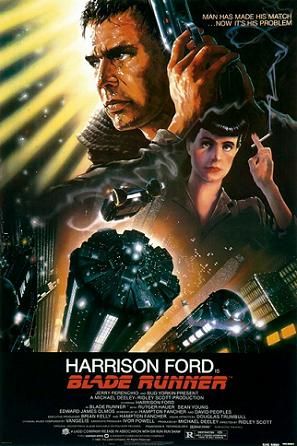

Blade Runner

Phillip K. Dick - Fabulist or Fantasist?

According to the dictionary, a fabulist is some one who tells a fictitious story which is intended to underline an important truth. Whereas a fantasist tells stories which can only exist in the imagination. I would say that the American science fiction writer, Phillip K. Dick (1928-82), is closer to the former than the latter.

Dick was the author of the now famous novel, Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep, later made into the highly successful film, Blade Runner (1982), directed by Ridley Scott. This is a great film, a classic of its kind, despite being subjected to the full Hollywood treatment.

But to begin with the novel. It would be wrong to dismiss Dick’s science fiction as mere pulp fiction. Rather he did much to elevate this genre to the canon of great American fiction. As Greg Rickman, one of Dick’s biographers, says, his writing is rich in ‘emotional acuity’. His daughter, Isa, completes this rehabilitation of her father. When asked about ‘Androids’, she reminds us that it poses the fundamental question: ‘What does it mean to be a human being?’

As for the film, Paul M. Sammon, author of Future Noir, argues that Blade Runner is the finest possible adaptation of the novel. Both the film and the book complement each other.’ Dick is concerned with an ongoing battle between the authentic human being and the automated android (as the author calls it). One could add that, given the technological world man has created so far, albeit within the straight-jacket of the market, the former are in danger of losing their humanity (not just individually, but also collectively).

As for the film, Paul M. Sammon, author of Future Noir, argues that Blade Runner is the finest possible adaptation of the novel. Both the film and the book complement each other.’ Dick is concerned with an ongoing battle between the authentic human being and the automated android (as the author calls it). One could add that, given the technological world man has created so far, albeit within the straight-jacket of the market, the former are in danger of losing their humanity (not just individually, but also collectively).

Therefore, Sammon continues, Dick’s android is a metaphor for ‘people without feelings, without empathy for others’; i.e. ‘their only goal in life is to satisfy their own cravings’. (In the film, the androids are renamed ‘replicants’, which The New American Dictionary (2012) defines, as ‘bio - logically produced synthetic human beings with para - physical abilities’.)

Dick is on record as saying, that ‘the replicants are deplorable, because they are heartless, completely self-centred. They don’t care about what happens to other creatures and to me this is essentially a less than human entity.’ Whereas director, Ridley Scott, says, ‘they are super humans with faster reflexes’. (But does Scott mean that they are superior to ourselves?) Dick goes on to explain that, Deckard, the main character, becomes dehumanised, because he decides to hunt down and kill 4 rogue replicants, in order to collect the bounty.

But is Deckard a replicant himself? Dick’s biographer, Jonathan Lethem, argues that this idea is certainly implied in the book. Moreover, ’The androids are able ‘to screw with other people’s heads.’ In Dick’s world, humans seem to be anxious about their status as human beings. They have access to something called an ‘empathy box’, wherein the viewer is encouraged to feel like a martyr being pelted by rocks. The message appears to be, ‘Look at what’s wrong with the real world around you! Wake up; take your emotional temperature….[Maybe] we’re all turning into androids’; that’s what Dick is saying, says Sammon.

‘You get a sense of Dick’s empathy for his characters, including the androids, who have no empathy’. But this is because their creators are human beings, who are making them in their own image. So it is not the fault of the androids! ‘Rachel [the female lead] is a quintessential Dick character…who thinks she’s human, but is actually an artificial person [however perfect, however beautiful], who then discovers the truth; therefore she wants to become a better person.’ This makes her more human than the humans, which is a typical P.K.D. philosophical conundrum!

The androids are programmed only to live for four years, although they have implanted in their brains a memory of their past life, which goes back to their earliest years. Hence they have a sense of their own unique identity, which is essential to all human beings. (Cf. Adorno’s idea of ‘the terror felt in the face of the crisis of individuality’, which is a characteristic of today’s societe de consommation or what he calls ‘late capitalism’. Most people seek to evade this anxiety ‘through the various forms of psychological regression in mass culture’. See later sections.)

Returning to Dick’s androids/ replicants: They are the creations of a giant corporation. In this regard, both the book and the film present a dystopian view of the future. By means of spectacular special effects, the latter depicts a degraded world, the aftermath of World War Three, which takes place in the early 21st century (i.e. about now!) The film tries to image what it would be like to live in ‘an ash heap of a world’. The Los Angeles of 2019 is heavily polluted by nuclear fallout. This is made worse by constant rain (cf. today!). Only the rich can escape this hell by emigrating to another planet. But those who choose to remain (e.g. the CROs of the big corporations) can still escape; because they live in penthouses high above the streets where people are forced to scrabble around in the mud.

Blade Runner is true to Dick’s story in other respects as well. For example it is clear that much of the earth’s animal life is virtually extinct. If you want a real pet, then you have to be rich! But the corporations are able to alleviate this lack by creating animal replicants (as well as androids), which are more affordable; such as an owl. (Given the owl’s status as a symbol of wisdom, there is a touch of irony here!)

In the novel, Dick also develops the idea of the callous cash-nexus (very much a feature of today’s society); but this doesn’t make it into the film for obvious reasons: Deckard only agrees to hunt down escaped androids, because if he is successful, he will use the generous bounty to buy real sheep and graze them on top of the penthouse where he lives - the air is cleaner there and the grass might grow - in order to impress his wife!

Lethem says, ‘the film is not a faithful adaptation…it doesn’t have to be. Blade Runner doesn’t have to capture every character and every scene in the novel.’ But what it can do better, by means of its visual effects, is ‘linger in this unbelievable, beautiful, strange and stimulating vision of the future’. This underlines the fact the two media have ‘different requirements’.

But let us give the last word to Dick himself: In a rare interview, just before his death, he says, ‘I was inspired to write the novel, because I was interested in the distinction between individuals who are physiologically human, but behave psychologically in a non-human, unfeeling way.’ He based his story on published research into the mentality of some leading Nazis. As a result, psychologists were able to draw up a general profile of ‘a highly intelligent human being, who is emotionally defective, [i.e.] psychopathic.

He concludes that his story explores the dramatic struggle between the two protagonists: Who will win, ’the humans or the androids? [But] Would we not become like them in the act of killing them? Compare this idea to the endless images of war on the TV news today. But this is presented without any real analysis as to who is to blame. Today we have live footage of Israel’s third invasion of the Gaza Strip in five years, wreaking death and destruction in its wake. At the same time, the Zionists are given free rein to tell lies about dismantling settlements in Gaza, whilst they continue to build more on the West Bank and in East Jerusalem.

So confident are the Israelis of a punishing defeat for the Palestinians, that the locals along the border with the Gaza Strip have got their sofas and cameras out, so they can sit in comfort whilst recording the carnage being done by their boys!

Meanwhile, the ubiquitous culture consumer’s appetite for violent entertainment continues to grow, in tandem with the new forms of mass communication; (the smart phone, etc.)

Phillip K. Dick and Ridley Scott have created a work of science fiction; firstly as a novel, secondly as a film adaptation. Both resemble a fable rather than a fantasy. This is because, in the first instance, the novel is a work of ‘emotional acuity’ (rather than mere pulp fiction). It raises the central question, ‘what does it mean to be human’; that is, in a society which is more fragmented and atomised than ever before? Thus we may ask, Where is humanity going?

These notes are based on the ‘Blade Runner’ film DVD box set (2012); in particular, the sections on the film’s ‘Inception’ and footage of interviews with Phillip K.Dick.

2014