But Things are Not Black and White

Despite my preference for art - and film making - which errs on the side of semblance/ innovative realism,

it is important to note that we must not see things only in black and white terms, i.e. the idea that only those

films which are based on the notion of semblance are ‘good’, whereas those which are based on mimetic

effects/conventional realism, are ‘bad’.

of course, this is not true. Nevertheless, I would still argue that when an artist - film maker - has a firm grasp of semblance, both

in theory and in practice, the end result is that the work in question is of superior quality. Indeed, apropos the medium,

it is usually the mark of distinction between a film which is made purely for entertainment, in which Hollywood production

values - the values of the market place - are uppermost, and one which falls into the category of a superior entertainment

or a work of art.

On the basis of the above, I want to compare two quite different films: The first one is Richard Linklater’s

On the basis of the above, I want to compare two quite different films: The first one is Richard Linklater’s

Fast Food Nation (2006). I shall argue that here we have an example of what I call ‘good; mimesis.

As usual, Linklater relies conventional realism; but he does so in ‘holistic’ way, which enables the

film to go beyond mere outward appearances. In the objective sense, every cultural product takes

on ‘a life of its own’, once it is released into the public domain.

Therefore it is open to interpretation; it may contain meanings that the artist/film maker, etc.

may not have been conscious of, which are not his/her explicit intention, and so on. This film

is a case in point. It is debatable that Linklater intended this film to reveal the hidden contradictions

within capitalism; such as the harmful effects that the simple meat burger has on society as a whole,

including the environment.

Most probably, he made this film, because it was a topical issue at the time. However, I think it is a worthy film, not because

of it’s form, because it is not particularly well-made; but because of the film’s content (or subject matter); once again, the

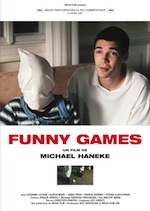

film is ‘holistic’ in character, which is most unusual for a film based on Hollywood production values. Indeed this is its greatest merit. On the other hand, Michael Haneke, another independent film maker, who has a reputation for

On the other hand, Michael Haneke, another independent film maker, who has a reputation for

making more serious films, gets it badly wrong in his film, Funny Games (1997). Paradoxically,

this is the result of an attempt to make a film, which is based on innovative realism. Unlike the

Linklater film, Haneke’s film is self-reflexive, at least up to a point. Indeed he adopts this

standpoint for quite worthy reasons: as a means to critique the way in which Hollywood

uses violence in a gratuitous fashion; that is, purely for entertainment purposes, which has

led to the current situation, whereby today’s audiences are addicted to fetishised violence.

When a film maker opts for innovative realism, this is usually a sign that he aspires to

making a film which has the status an art film.

But in my opinion, Haneke has failed here (Therefore perhaps Haneke later realised that his 1997 film is a failure in this respect. On the one hand, it has not made a big impression on shrinking art house audiences; on the other, it has flopped at the box office. This might explain why he has since remade funny Funny Games. (But for what kind of audience?) I have not seen the latter, therefore I will restrict my comments to the earlier version. (See below.)

To begin with the Linklater film: I would argue that the only way in which mimesis can play a positive role apropos the cinema - is when conventional realism, simulacra or naturalism strives to present a totality or world view, as opposed to fragments of reality, which have an air of authenticity, at least in terms of surface appearances. Such an approach might not be the most artistic way of doing things, but at least such a work has the chance to succeed in challenging the status quo. This is exactly what Linklater has achieved in Fast Food Nation. It is all the more surprising, because his earlier films are concerned with far less weighty subjects (e.g. Before Sunrise and its sequal, which might be described as superior ‘rom-com’ movies).

Fast Food... is constrained by Hollywood production values, whose ultimate aim is an entertaining film which will do well at the box office. Accordingly this film contains the following: (i) It is based on a conventional narrative; (ii) It includes a love interest between a pretty young woman and a handsome young man, who just happen to be illegal Mexican immigrants; (iii) There are cameo appearances by big stars, including Bruce Willis. Yet despite everything, the film has gravitas. At the very least, it makes a statement against the slaughter of animals just to produce fast food; quite often, for people who are already overweight. This might be considered both an unkindness to animals and also immoral; given the fact that right now there are 1.5 billion people in world who are either hungry or starving.

But in my view it could also be seen as an anti-capitalist film. This is because, while it is a run-of-the mill Hollywood drama, at the same time it is a sort of ‘documentary’ of the meat industry as a whole. Yet it is not a conventional documentary, because it is a drama as well; but at different points and not in any chronological fashion, it reveals to the audience the whole industrial process, from the animals grazing in the fields, all the way down to the consumer in the burger bar. One could argue therefore that the film functions as a paradigm for the workings of capital in general; even its subject is an unglamorous one; i.e. a meat packing plant in Texas.

The plant itself is at the centre of all the relationships between the dramatus personae, as well as the action. At one stage we meet the rancher who supplies the animals, which are necessary to start the whole process. He has long since become a pawn of the company, which has a monopoly and is able to dictate its own terms to the suppliers of its raw materials. As for the main characters in the story, they are representative of the whole array of workers, overseers, managers, the producers of new products for the company, retail sellers, and so on. The lowest grade workers are the young Mexicans, who work on the production line. In order to get promotion from the worst jobs, such as removing the organs from the carcasses, the foreman forces the girls to have sex wuth him. By watching the meat being processed on the assembly line, we learn how real shit gets into our beef-burgers. It happens because the line is going too fast for the workers to keep up.

So there is many a slip of the knife when the animals are being gutted. Moreover, as a result of speedups, sometimes workers get caught in the machinery and are horribly maimed. Upon learning how it is inevitable that shit will end up in a beef burger, an idealistic manager starts to investigate. But it does not take long before he is reminded that he is putting his job on the line. Before long, he stops his investigations after being offered a hefty bonus. In another scene we see a nearby river which has been polluted by waste products from the plant. Finally we see low-paid workers selling cheap, ‘wholesome’ mega-burgers to a gullible public in a fast food retail chain that could be Mac Donalds.

Towards the end, however, the film takes a radical departure from its Hollywood production values. This is achieved in two ways: Firstly, in a horrific climax, Linklater suddenly introduces real documentary footage of animals being slaughtered as they enter the meat works. He forces us to watch an everyday event, which we would rather not see, lest it puts us off our next steak. As soon as the animals enter the factory, they are stunned, beheaded and gutted within the space of a couple of minutes. The effect is truly shocking. (N.B. Here we see stun guns being used for real. In this regard, Fast Food Nation is a far cry from the Cohen Brothers’ No County For Old Men, wherein a serial killer, played by Javier Badem, uses a stun gun to kill a score of innocent people, because they had the misfortune to cross his path, whilst he searches for some stolen drug money. But if Badem is meant to be ‘the angel of death’, then most people don’t see it that way. When I saw No Country... I heard the audience laugh at Badem’s antics, despite the gruesome simulacra of his killing spree. Such are the fruits of Hollywood violence, served up as an entertainment, cheap sensationalism, which is largely forgotten once the audience leaves the cinema.)

The second radical departure for a standard Hollywood feature film, which is the flavour of the month, etc. is the fact that Linklater’s film is open-ended. The final sequence shows the next wave of illegal immigrants, a group of young Mexicans being smuggled across the border en route to becoming cheap labour for the meat packing company. They do the jobs that no one else wants to do, because they have no choice. But this is not before we see a group of idealistic young college students taking their first steps towards direct action in protest against the company. Although they fail to liberate the cattle from their fate, it is a promising start!

So there is always the exception to the rule. Linklater was able to use Hollywood studio money in order to make a film like Fast Food Nation. Despite his reliance on conventional realism (possibly as a quid pro quo?), he largely succeeds in his aim: i.e. he compels us to question the status quo. Whether he intended this or not, it is possible to construe a deeper level of meaning, i.e. at a superficial level, it might be a drama set in a meatpacking plant; but it also functions as a paradigm for the capitalist mode of production itself.

Fast Food Nation highlights the contradictory relationship between the means/end rationality of the production line, i.e. as the most efficient way to accumulate capital, and the effects that this has on the workforce. It shows how ‘the rationalised and mechanised labour process’ fragments and alienates the workforce, as well as the consumer of the finished product or the mega-burger; thanks to the efforts of the advertising department, the latter becomes an irresistably tangible example of commodity fetishism. That is the surprising outcome of a film which is entirely focused on a meat packing plant, including an assortment of erstwhile ordinary characters, unglamorous as the subject may be. If nothing else, Linklater has succeeded in persuading more than a few people not to order another beef-burger when they next visit a fast food restaurant!

Conversely Funny Games is an example of ‘bad’ semblance/innovative realism. To be precise, Haneke combines conventional realism, i.e. scenes in which the antagonists use violence in a horrific and very convincing way, with the occasional self-reflexive scene, in which one or the other of the random killers breaks off from his ‘work’ in order to speak straight to camera. I begin with a review of the film by Geoff Andrews, a distinguished ‘Time Out Critic’. He writes :

‘Continuing the fascination with violence and its representation evident in his earlier films, Haneke’s movie may be shocking, but it is also serious. A couple and their young son arrive at their lakeside holiday home, only to have it invaded by two strange, ultra-polite young men, who turn out to be sadistic, homicidal psychopaths. No explanations are offered for the killers’ behaviour, rather through their regular asides to the camera, and by occasionally disrupting the otherwise ‘realist’ narrative, Haneke explores both the emotional and physical effects of violence, and interrogates our own motives in consuming violent stories. Amazingly, very little violence is actually seen; we hear its perpetration and witness its aftermath, which (though no less disturbing) is absolutely crucial to the responsible treatment of such a horrific subject. Brilliant, radical, provocative, it’s a masterpiece that is at times barely watchable.’ (Time Out Film Guide, 2006.)

My own response to this film is somewhat more critical: Firstly, I found it unwatchable in its DVD version, because it is so sickening. But at least I was able to fast-forward the film to the end, in order to see what happens. Indeed, in the final scene the two young men are seen introducing themselves to an unsuspecting neighbour, the implication being that they are serial killers, who kill just for fun. Haneke’s raison d’etre is to challenge people to ask themselves why they want to be entertained by violent films, in which the violence is depicted as realistically as possible, except the audience knows that the scenes they see on the screen are being acted out. But given the fact that this film does not purport to be appreciated at a deeper level, since it eschews symbolism,metaphor, irony, etc., most of the time we are encouraged to suspend disbelief, until the film ends.

The problem with Haneke’s raison d’ etre is obvious. He falls between two stools: firstly, it does not satisfy the critical viewer; i.e. those of us who are aware of the way in which Hollywood has exploited the pornography of violence and indeed transformed it: Today the pornography of violence has ‘advanced’ to the stage of highly stylised or fetishised violence, complete with slo-mo bullets and tearing flesh, lots of gore, etc. The critical viewer already knows that films which rely on crude sensationalism are able to profit from this, because they appeal to man’s inhuman side or his animal instincts. This sort of thing allows the undiscerning viewer to release his pent-up frustrations with living in the real world; albeit the danger is that, even if it only affects one in a hundred thousand like this, a single individual’s real-life sense of impotent rage and insignificant presence in society might be wound up to a point, where he (because they are mostly male) might suddenly snap and go on a killing spree in a nearby shopping mall or high-school campus, etc.. Therefore is there any need for the critical film goer to see such a film, since it is only preaching to the converted. (On the other hand, Haneke might be trying to tease out a latent desire for the pornography of violence, etc.; even in the dark recesses of this category of the discerning film goer!)

As for the majority of film goers, i.e. those who eschew all critical thought, whose only need is for visual images which stimulate their basic instincts, their desire for crude sensationalism, etc., then Haneke’s raison d’etre is lost on them. They are going to be drawn towards this film, because it purports to be the same as any other film which belongs to the category of violence; given the way in which Funny Games has been promoted by distributers within the film industry. For the majority, violence is only entertainment. Paradoxically, however, for some, the fact that the violence in this film is not shown in the most graphic form, means they will come away disappointed. They will criticise this film because it is ‘not violent enough’, but for no other reason; i.e. they won’t start thinking that ‘there is too much violence in the real world and decide that something should be done about it’.

Therefore Haneke’s ‘Funny Games’ can serve only one - or perhaps two - purposes: It has certainly earned him a reputation as a controversial film maker in intellectual circles. As a result of the advertising hype which surrounded the film’s release (which continues, following its release onto DVD), Haneke - or the film industry - has made quite a lot of money, even if it was not a smash hit. Therefore Haneke had the opportunity to break into the mainstream. After Funny Games, he went on to make a feature film called Hidden, which was an bigger success financially. Thus Haneke’s raison d’etre is, to say the least, a very contradictory one. Arguably, it is a complete failure.

Leni Riefenstahl

But this immediately raises another problem: The beauty of form can also be used to justify a subject (content), which in reality is both ugly and evil. Leni Riefenstahl’s notorious film, Triumph of the Will (1934) is a case in point. This was a documentary film commissioned by the Nazis in order to commemorate the Nuremberg Rally of that year. By so doing, she uses a striking modernist form, via her mastery of the montage technique, in combination with oblique camera angles, the use of light and shadow, etc, which technically speaking, is comparable to Eisenstein’s aesthetic in Battleship Potemkin. But whereas the latter’s film, as one commentator has said, is about both ‘the essence of film-making and the essence of revolution, in Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will we see the glorification of the Nazi regime, which would go on to plunge Europe into another world war and culminate with the Holocaust (Genocide by industrial means). Therefore in this case, we do not have the Hegelian desired outcome, whereby ‘the artwork is the conquest of the ugly by the beautiful [via] the successful integration of the former into a harmonious totality’.