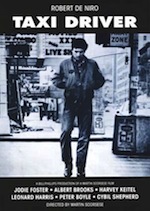

Taxi Driver

The Time Out Film Guide (2006 edition) entry for Taxi Driver argues that this film is widely claimed

as a masterpiece for two reasons. Firstly, it is a realistic portrayal of the violent ‘mean streets’ of New York,

enhanced by Bernard Hermann’s ‘most menacing score since Psycho. Secondly, thanks to De Niro’s

performance as the principal character, Travis Bickel (N.B. in which method acting is strongly to the fore),

this film is also a ‘really intelligent appraisal of the fundamental ingredients of contemporary insanity’.

frenzy of violence at the end. We see people shot by ‘slo-mo’ bullets; bodies

fly and the blood flows across the screen, as if this was a carefully

choreographed ballet.

But, as the Time Out critic says, it ‘doesn’t seem to be cathartic in the now predictable fashion

of the ‘new’ American movie’. This is clearly a reference to the current portrayal of violence

on screen, not so much as the real thing, but as a simulacra, as a means to further stimulate

the senses, i.e. create sensual excitement for all the wrong reasons, thanks to the latest

digitalised special effects.

In this regard, Scorsese’s film established a benchmark for future film makers to improve upon, who are similarly obsessed with violence, as well as the technological means to show case it.

Hollywood’s long obsession with violence has led to its twin: an obsession with the latest technology in film making (especially

the new steady-cam cameras, etc.) as a means to facilitate this obsession. It finds its culmination in fetishised violence. Despite

the fact that the depiction of violence has become more stylised, a simulacra of the real thing, formalism in this case does not

lend itself to semblance, but stays firmly within the category of mimesis. The main reason for this is that film makers allow

themselves to remain the servants of Hollywood and its production values. In Scorsese’s case, this is a pity, because he is so

knowledgable about the history of film, especially the contribution of European cinema and its auteur tradition. (Consider, for example, his excellent documentary about postwar Italian cinema, which pioneered the era of neo-realism.)

As a result, what we get is cinematic violence, whose primary aim is to entertain an uncritical mass audience, whose

expectations are very narrow. Therefore they do not want to think about wider issues; e.g. the link between individual violence

and the fact that we live in a class society, which is based on violence: When one class seeks to extract the surplus labour

from another, in times of crisis, ignorance, the desire for distraction, submission to the rule of capital on the factory floor,

etc. is an insufficient form of social control. Therefore the economic basis of society has to be underpinned by violence,

beginning with the state and its laws. The paramount aim of the ruling class and its laws is to legitimise the use of state

sponsored violence in defence of private property (at home and away). Of equal importance is the fact that under capitalism,

economic violence is a given, even if most people don’t see it; e.g. at this moment in time, there are 1.5 billion poor people

on this earth, who are either hungry or dying of hunger-related diseases. But these self-evident truths, remain hidden from

view by the great and the good, as well as the many, thanks to alienated labour and its ‘mind-forged manacles’.

Some might argue that my response is well ‘over the top’ for a film which is, after all, ‘only an entertainment’! But surely this is THE problem, viz. violent entertainment in a violent world. Hollywood rules the world of entertainment. But it is a manufacturer of false needs That’s why most people who watch Taxi Driver (including many film critics), do not bother to think about the film in these terms. They would rather talk about De Niro’s paranoid posturing with a gun in front of a mirror, and especially the film’s violent climax; not just as a 'dramatic' spectacle; but also from a technical point of view. Despite Scorsese’s use of new technology in order to depict violence in an innovative way, he does little to explain why Bickel embarks on his violent rampage,. All we have is the knowledge that he has a growing sense of isolation and frustration.

Despite its slo-mo violent climax, for most of the time, Taxi Driver relies on conventional realism or the attempt to be a mirror image of reality (cf. mimesis). Only in this way can it be argued that it is a vehicle for social criticism. Consider the following comments in the ‘BFI Classics’ essay on the film:

The reviewer attempts to justify what he describes as the ‘carnage’ at the film’s climax, before going on to say that ‘the imagery of the [Vietnam] war and...the violence at home gave a moral justification to the film-maker.’ Later he says, ‘the Vietnam war also intensified America’s obsession with lethal weaponry.’ But all the emphasis is on the main character, Travis Bickel, who is described as a ‘new anti-hero’, with ‘a pathological relation to violence’ as the ‘answer to his castration anxiety’, which ‘he barely troubles to hide’. His misogyny is also clearly in evidence. [See below.] Whereas his alleged Vietnam experience, which might have led to a post-traumatic personality disorder - as it is now called - is certainly not chalked up for the audience. (The best Scorsese can muster is a timid attempt to link Travis with Vietnam via a fleeting glimpse of a North Vietnamese flag in the corner of his cluttered basement apartment.) Similarly there is barely a mention of his racism; that is, until Travis undertakes to brutally ‘execute’ a young black petty-criminal in a grocery store. All of this, of course, enables the reviewer to draw attention to the acting of rising star, Robert de Niro, who is more than convincing as a psychopath on a vigilante mission to ‘wipe the scum off the streets of New York’.

Therefore what we end up with, at best, is an ambiguous message as to the reasons why the film erupts into ultra-violence its end. Is it because Scorsese is trying to make a social critique by minimalist means or mimetic effects; i.e. simply by reproducing what happens on New York’s mean streets; or is it merely for the sake of violence as spectacle? To reiterate Adorno's point, shock effects in art should not be related to pleasure; because it renders the self, in its moment of liquidation, unable to see even the slightest bit beyond its own ‘prison’ of alienation. What is needed here is not distraction, but the highest concentration.

Arguably, what really motivates Scorsese is his desire for crude sensationalism: The BFI’s reviewer of Taxi Driver goes on to describe the final carnage ‘as voluptuous as anything in American movies and all the more so because of the sense of repression that pervades the film until this moment.’ But we should not take his word for it: Script writer, Paul Schrader adds that the release of all this pressure is ‘the psychopath’s Second Coming’; while director, Scorsese muses, ‘I like the idea of spurting blood....It’s like a purification.’ (Note the Christian - catholic - symbolism here!)

Is this the price which had to be paid by over two million Vietnamese, slaughtered by the American military, most of them civilians; i.e. so that western consumerism can have the luxury of watching violence as a form of entertainment? (At least Coppola hits the right spot in Apocalypse Now. Consider the scene where a U.S. airforce colonel leads an airborne assault on a Vietnamese village, so that his men to go surfing as a reward for capturing it!) Nevertheless, Taxi Driver has become a seminal movie, from which a long line of Hollywood thrillers featuring psychopaths in the leading role, are descended.

At no stage does Scorsese offer his audience a ‘negating moment’, e.g. a glimpse of redemption - not a God-given one - but a human capacity to learn from experience; so that a man might become more human; not less; some one at least! In this regard, the director and his script writer, etc. do not have to paint a picture of utopia; e.g. provide a conventional Hollywood happy ending. But simply by including some kind of negating moment, a film is able to say a clear ‘no’ to present society. Thus it has the potential to resist all attempts to be co-opted into the ‘culture industry’; even from within the heart of Hollywood itself. Taxi Driver does not do this.

One such negating moment could have come up in Travis’ attempted relationship with Betsy the political campaigner (played by Cybill Shepherd). After a truly heroic ‘chatting up’ scene, Travis squanders his chances of a successful romance in one go, when he takes the woman, whom he worships like an ‘angel’, to a porn movie. On one level, this is just plain stupid, says our reviewer; but on the other, at an unconscious level, ‘although he could never admit it to himself, taking Betsy to a porn movie is a violation, a psychological rape. When Betsy gives him the cold shoulder, he redirects his desire to the [child prostitute] Iris.’ Thus the film suddenly lurches towards the chain of events which will lead to the massacre.

As for the canon of great films, some of which confront violence and the reasons for it head on, e.g. Battle For Algiers, I am unable to include ‘Taxi Driver’ , precisely because it is a ground-breaking violent vigilante movie. The former rightly belongs to the art-house and political cinema: It poses big questions for the audience to ponder. The latter does not. Despite its conventional realist form, some superb night photography of New York’s neon-lit streets; not forgetting its stimulating neo-jazz sound-track, Taxi Driver is trumpeted as a masterpiece for all the wrong reasons.