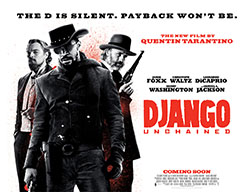

Django UnChained

Critique of Django UnChained

On Thursday, 10th January, 2013, two news items caught my attention. One was about what I call quotidian economic violence; the other was an interview with Hollywood director, Quentin Tarantino, about his latest violent movie, Django Unchained.

BBC2’s Newsnight revealed the government’s plans for the next round of public

BBC2’s Newsnight revealed the government’s plans for the next round of public

spending cuts. But what should be cut? Education, health, defence? Defence, no!

That’s been cut already and the UK has obligations to its allies. So it’s got to be

welfare for the poor, the disabled, the sick and the elderly. Take the latter. People are living longer (the well-off maybe; but not the poor!) The cost of old age pensions is rising, whilst the working population is shrinking.

Therefore, to make ends meet, the government has to raise the retirement age for everyone, regardless of different degrees of toil. Means testing universal benefits is also being considered.

(But not actively, since this would mean cutting welfare for the rich!) Once again, we hear the mantras: ‘Britain has to live within

its means’, ‘There is no alternative!’, and so on. But the proposed reform of the state pension means that people who have

worked all their lives can no longer look forward to a comfortable old age.You may as well die early (unless you’re rich, of course

After 250 years of modern capitalism, Marx’s basic idea - that human life and happiness should be its own end - eludes the

consciousness of most people. Rather abstract notions, such as as the need to ‘balance the budget’ are widely accepted as the norm. Few people question the concrete fact that the trillion pounds which the UK government spent in order to bail out a tiny handful of bankers, has to be borne by the taxpayer, the majority of whom are working people. That is what austerity really means and it will last for years to come. Yet in 2007-8 it was the bankers who triggered the biggest crisis of capitalism since the 1930s. They are still paying themselves huge bonuses, even though some banks are still losing money!

Earlier that evening Channel 4 News ran an interview between presenter, Krishnan Guru-Murthy and Quentin Tarantino about his new movie. Django Unchained. But why was the launch of a Hollywood film newsworthy? Is it because it is ultra-violent? Not really, because that’s normal these days. Rather its release coincided with yet another gun massacre in the United States. Therefore Guru-Murthy wanted to know why Tarantino had made another violent movie and whether he has ever considered there might be a link between violent entertainment and violence in the real world? Tarantino avoided the question, saying that he had always wanted to make a movie about slavery and to ‘give African males a black western hero’; to ‘empower’ them by showing them ‘give blood for blood.’:

G-M: ‘So its’ just another revenge movie....It doesn’t stand out from all your other movies.’

T: ‘It’s about slavery and that’s still a controversial issue in the United States.’

G-M: ‘You like violent movies.’

T: ‘I dunno....I think it’s good cinema....when cathartic violence happens....paying back blood for blood.

G-M: ‘It’s OK to enjoy violence?’

T: ‘Yep!’

G-M: ‘But what about the link between violent entertainment and real violence’ [Note, The recent massacre

at an elementary school was still a topical issue. The film’s opening in the united States had to be delayed as a result!]

T: ‘I refuse to answer your question.’

G-M: ‘But your leading man, Jamie Foxx says there is a link!’

T: (agitated) ‘Look I’m here [in the UK] to sell my movie.’

Guru-Murthy persists with his link question.

T: [annoyed] ‘I’m shutting your butt down!’

Recently a number of American actors appeared in TV ads. calling for stricter gun control laws in the USA, e.g. a ban on assault rifles, the weapon of choice for mass murderers. But the opposition - led by the National Rifle Association (NRA) - was able to ex- pose some of them (including Jamie Foxx) for acting in films based on gratuitous violence. The latter sells more tickets at the box office, e.g. a movie like Django Unchained.

Allegations of any sort of link between violent entertainment and violence in the real world, especially gun massacres, reminds me of the work of the critical theorist, Theodor Adorno (who continues to be ridiculed by many marxists). Writing to his friend, Walter Benjamin,in the 1930s, he argued that the laughter of cinema audiences is ‘full of the worst forms of bourgeois sadism’. It started with cartoons. Now Hollywood spends billions of dollars turning a comic-strip figure like Batman into a movie. All harmless fun until last year: A man dressed as Batman leapt onto a cinema stage and massacred 14 members of the audience. Adorno is perhaps best known for his theory of the ‘culture industry’; characterised by ‘distracted consumption’. (Cf. serious art, which requires con -centration and an understanding of its form and content.) The audience is infantalized. But ‘their primitivism is not that of the unde -veloped, but of the man forced into regression’. 1

This may explain why the educated middle class also enjoy violent action thrillers (or trivia). In response to the stress and degrad -ation of bourgeois life, people feel the same need for stimulating distraction. This includes people on the left. I am not immune from such entertainment myself! But entertainment, per se, is not the problem. After all, it was Brecht who pointed out that suc -cessful art has to be entertaining, well as thought provoking; i.e. compel us to challenge the status quo. Film has the potential to do this. But it does so less and less. At best, a lot of Hollywood entertainment merely discourages critical thought. At worst, people actually enjoy watching simulations of people killing each other; not just in ones and twos, but repeatedly. (When I saw the film No Country for Old Men, I lost count of the number of killings. I had no idea that somebody would be murdered every few minutes; otherwise I would not have wanted to see the film. Yet this is considered to be one of the Coen brothers best films!)

On the other hand, Adorno reminds us that, ‘in a communist society, work will be organised in such a way that people will no longer be so tired and so stultified that they need distraction.’ 2 As communists, we must not forget that goal. Neither should we be com -placent about the the culture industry. On the one hand, it is a reflection of the violence of late capitalism in all its forms. On the oth -er, it is beginning to play a more active role in society. It is an aspect of the decay of bourgeois society, in general, and the working class, in particular (i.e. as a class, both in terms of its self-organisation and consciousness). Other factors then come into play: First -ly, the fragmented, atomised individual psyche is more open to new fads and fashions, which are increasingly perverse or deprav -ed. Secondly, in the age of the internet, the new technologies of mass reproducibility have democratised creativity (both ‘high’ and ‘low’). Therefore what passed as Hollywood entertainment, violent video games, as well as hard-porn, can now be imitated by the masses and published on-line.

At the same time, the culture of violence spills over into violence in the real world: Bored teenagers film acts of bullying on their mobiles and then share their home-made violent images online. In the United States, history and ideology also play a role: America is cursed by the ‘sacred’, constitutional right of its citizens to bear arms. * This might have made sense 200 years ago, when civilian militias were needed in case of another English invasion. But today Americans live in fear that one of their own deranged citizens will exercise this right in order to murder them. After last year’s massacre of 26 children and teachers at an elementary school in Connecticut, children are now involved in ‘lock-down’ exercises. (Cf. exercises in case of a nuclear attack during the Cold War.) Teachers use analogies from the movies or video games to describe a possible assailant, such as the ‘masked man’. If any -thing, the American people’s addiction to violence has increased.

Therefore the NRA argues that the best defence is to have more ‘good’ guys with guns to take out the ‘bad’ guys. Teachers should be armed. It has the support of the Republican majority in the lower house of Congress. Moreover gun sales in the United States are big business. Hence there is little chance of new gun control laws any time soon. More massacres are inevitable.

Days after the Tarantino interview, Django Unchained was chosen as the film for discussion on BBC2’s Friday Review Show. But he need not have worried about this panel of educated ‘critics’. They all gave it the thumbs up! It doesn’t matter if the movie is hist -orically inaccurate. In order for the film to end with a blood-and-gore-fest, our black hero would have needed a modern-day as -sault rifle, not six guns, etc. It also helps to have a ‘politically-correct’ story-line: black slave reeks revenge against his brutal white slave masters. In this regard, Django Unchained bears no comparison with Pontecorvo’s film, Burn (1968). The latter was inspired by the only successful slave revolt in history, i.e. the one led by Toussaint L’ Ouverture on the island of Haiti in the early 19th century.

There is plenty of violence in both films. But the former is an example of an entertainment which uses a good story as a ‘hook’ for gratuitous violence. This ensures that it will sell well at the box office. Whereas the latter film is a historical epic, which is artistic in form; but the film’s subject (or content) is just as important; because it explains the causes of the revolt, as well as what happened. At the same time, it is accessible to a wider audience. Therefore it is an example of serious entertainment; except it has long since been forgotten; especially by those Review Show film critics! Arguably they have exchanged their own ‘expertise’ for a ‘regression’ of thinking, in the name of box office entertainment!

Another explanation for this ‘regression’ might be found in an article which appeared in the Guardian Review a few weeks later. Reg -ular columnist, John Dugdale revealed that BBC2’s Friday Review Show is to be moved to BBC4, ‘pending a decision about its fut -ure’. This is ‘executive code for likely death’: ‘What [this] relegation symbolises is a dual...BBC unease: about...all cultural forms, except art and music - [i.e.about ] criticism on TV....When the tone increasingly required by presenters in arts output...is boyish or girlish enthusiasm, even attempting neutral analysis, let alone voicing dissatisfaction, means you [are an unwelcome] sourpuss.’ 3

So what is going on? At the risk of being a Jeremiah, perhaps all this is symtomatic of the decline of bourgeois culture in the broad est sense of the term? In the current period of deep crisis and decline of the capitalist system, epitomised by the worship of the profit motive in all things, including art and entertainment, cultural criticism - as well as culture (associated with the arts) - is also in decline.

This is worrying when compared to past eras, even the ‘midnight of the century’ or the Stalin/Hitler era: Despite everything, there was still a healthy debate being conducted between critical theorists, such as Adorno and Benjamin. At the same time, the surreal-

ist poet, Andre Breton collaborated with Trotsky in order to write a manifesto, based on the theme: ‘The freedom of art for the Revo -lution - The revolution for the freedom of art’. This is a far cry from today.

The decay of cultural criticism is a huge setback for marxism, which is in desperate need of renaissance (and not just for its own sake!) But for such a revival to happen, two things are required: Firstly, the prevailing theory of post structuralism - the ‘logics

of disintegration’ - along with its cynical, self-serving zeitgeist, aka postmodernism, has to be challenged. The latter, for example,

provides an intellectual fig leaf for the culture industry, linked to that newer phenomenon - or is it older? - the celebrity industry.

Taken together, they both reflect and reinforce what Marx calls ‘the inverting power of money’. The latter ‘transforms...nonsense

into reason and reason into nonsense’, etc. 4 Secondly, such a fightback can only be achieved by means of a determined struggle

to rehabilitate the tradition of all totalising theories of reality; such as those of Hegel, Kant, Schiller and Marx in the 19th century

or Freud and the critical theorists in the 20th century. Then it would be possible, once again, to develop a real critique of a bourg- geois culture in the epoch of its decay.

Take, for example, Marx’s observations in his Theory of Value about the relationship between entertainment and the market. To paraphrase Marx, he says: '[Whoever] fabricates [films] under the direction of [Hollywood, etc. is merely] a productive labourer; for his product is from the outset subsumed under capital, and comes into being only for the purpose of increasing that capital.' 5 It is

not an activity of his nature. (Cf. independent directors, such as Pontecorvo in the 1970s or Ken Loach today. Old labour or not,

he will be remembered - by some - for films like Kes!)

* Re 'The Right to Keep and Bear Arms':

In the epoch of capitalist decay, for communists, a discussion about the maximum programme, becomes more problematic. This is especially true with regard to the question of the right of the working class - or the people - to take up arms. Consider two famous historical examples: firstly, the Paris Commune of 1871; secondly. the Second Amendment to the American Constitution of 1791. There are, of course, important differences between the two. In the case of the former, the working class of Paris rose up against the attempt by the Theirs regime to restore the bourgeois state, following France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian war. As Marx writes in his pamphlet on The Civil War in France: 'The first decree of the Commune was the suppression of the standing army, and the substitution of the armed people.' This was a social revolution in the making, which, as always, must begin with a situation of dual power between the contending classes. The masses have the right to defend themselves against the bourgeois counter-revo -lution, etc. (What happened next is not our concern here.) In the case of the latter, we are talking about a war of national liberation - or its aftermath - not a social revolution. Less than 20 years before, the American people had fought a successful war against Brit -ish rule. But both the government and the people feared that the British would try to overthrow the new republic once again (or some other colonial power). Hence Congress passed the Second Amendment, which states: 'A well-regulated militia, being neces -sary to the security of a free state, the right to keep and bear arms, shall not be infringed.'

But in the intervening period, especially during the era of late capitalism, American society has undergone a deep and qualitative decline. The common bonds of unity of the oppressed masses and their leaders, circa 1791, have disappeared. What we now have is a mass consumerist/mass media society, based on neo-liberalist economics. The hidden reality is as follows: We have the relent -less atomisation of the masses, whereby everything (almost) is governed by the 'callous cash-nexus'; along with rising inequality between rich and poor. This can only lead to greater alienation and the dehumanisation of America's citizens. Concretely, for with -example, more and more drugs are coming across the US/Mexican border. Hence there are more drug-elated killings, especially in the ghettos, i.e. poor against poor; as well as an increasing number of gun-massacres perpetrated by mentally deranged individ -uals. In a single year, an average of 30, 000 people are shot dead in the United States; more than the number of people who are killed on the roads. Last, but not least, all of this finds its reflection in violent entertainment. Thus a lot of ground will have to be covered before we can arrive at the position the USA found itself in, circa the second amendment of 1791; let alone that which arose in Paris at the beginning of 1871!

In the light of the above, is it a good idea for communists to cite the Second Amendment as means to raise the maximum pro -gramme, viz. the right of the masses 'to keep and bear arms', albeit in an abstract way? This can only be done by acknowl -edging, firstly, that there is a stark contrast between past and present; secondly, that this has to be taken into account whenever we raise the demand of arming the working class. As far as the American masses are concerned, it is obvious that they will have to won over to communist ideas. Therefore, in our propaganda about arming the masses, we should start by acknowledging the 'clear and present danger' which is posed by a people who already have the right 'to keep and bear arms' in a society which is becoming more and more dehumanised. We would have to point out that the masses need to acquire an adequate or 'communist con -sciousness'. The German Ideology defines the latter 'as the necessity of a fundamental revolution'. Otherwise, the armed masses are not going to exercise their power in a revolutionary manner. They will use their arms for all the wrong reasons, as at present. Apart from the right of the people to bear arms, it would also be necessary for communists to proselytise the fact that, the masses would also have to to be won over to the idea of overthrowing the state, beginning with the abolition of the US armed forces and the state police. After all, since 1945, the former, as the most powerful military machine in world history, has been deployed, ex -clusively, as the brutal oppressor of the rebellious poor elsewhere in the world. Similarly, at home, the state police continue to kill many unarmed blacks (in particular). Hence, in due course, the armed forces and the police must be replaced by a popular militia; at least until a universal classless society has been established, whereupon the need to protect life and property, as well as to go to war, would become redundant.

For communists to justify the Second Amendment, all of the above would have to be taken into account. In short, we must make it absolutely clear that the American masses have to exchange their patriotism and wage slavery for the ideas expressed in the Com -munist Manifesto; in particular: 'All that is holy is profaned, and man is at last compelled to face with sober senses his real condit -ions of life, and his relations with his kind.' But we are nowhere near that yet. That is why at this point in time, the whole question of the right 'to keep and near arms' is drought with difficulty.

Notes:

1. Adorno, Letters to Benjamin, written in the 1930s, in Aesthetics and Politics, quoted by Eugene Lunn in Marxism and Modern -ism,University of California Press, 1984, p 156. Adorno’s theory of the culture industry has its origins in these letters, first published as an essay entitled, On Popular Music in Studies in Philosophy and Social Science, 1941. Adorno scholars, such as his student, Rolf Tiedemann, argue that Benjamin’s positive take on ‘distracted’ collective reception ignored the totalitarian policies of the Nazi state, wherein individuals are manipulated en masse by officially sanctioned art, e.g. the films of Leni Riefenstahl. (Cf. Stalin’s Soviet Union.)

Today, it could be argued that the culture industry, i.e. Hollywood and the ‘free’ market perform the same role, but not in a conspira- torial way. Defenders of Benjamin’s theory of mass reception argue that Adorno is guilty of being a conservative cultural critic. But Benjamin’s own position is ambivalent and inconsistent. (See 'Essays' section.)

Adorno’s ideas about distraction and regression are developed further in Dialectic of Enlightenment (1944). (See Kai Hammermeist -er, The German Aesthetic Tradition, Adorno, Part Three, Cambridge University Press, 2002, p 200.)

2. Lunn, p 156.

3. The Week in Books, Guardian Review, 2nd March, 2013.

4. Marx, Economic and Philosophical Manuscripts, in Marx Early Writings, Introduced by Lucio Colletti, Penguin Books, 1992, pp 378-9.

5. I.I. Rubin, Essays on Marx’s Theory of Value, Black Rose Books, Montreal, 1982, pp 262-3.